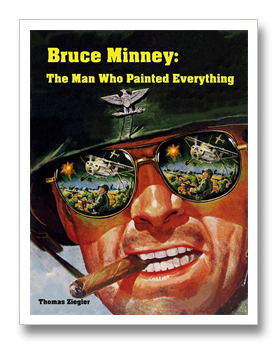

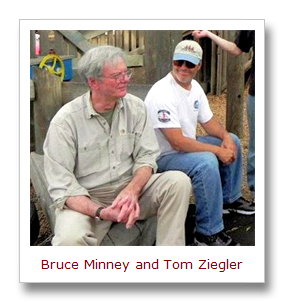

Editor’s Note: This is the third and final installment in a series of special guest posts by Tom Ziegler, author of the fascinating, lushly-illustrated new book BRUCE MINNEY: THE MAN WHO PAINTED EVERYTHING.

Here’s a link to the first post, and here’s a link to the second, in case you missed them.

“Bruce Minney: The Man Who Painted Everything”— Part 3, by author Tom Ziegler

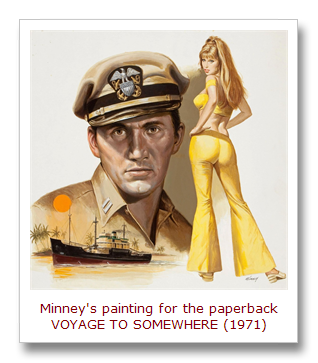

When Bruce was doing illustrations for men’s adventure magazines, he didn’t think that they would be his legacy.

He always wanted to be a fine artist. The illustrations were a job that paid the bills.

Doing the interviews for the book was unsettling for Bruce.

He had put this period of his life into a box that hadn’t been opened for a long time. He has mixed feelings about the illustrations.

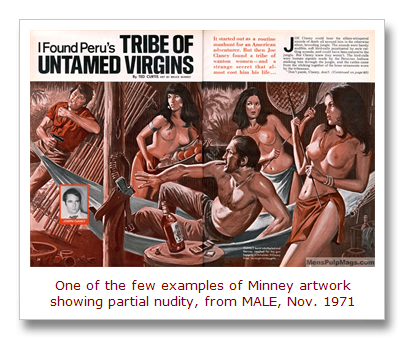

He is quite proud of a few of them. Others he would rather forget.

He says he was never embarrassed doing men’s adventure magazines, but that he never really felt proud of it either.

Seeing some of his work 50 years later has changed his perceptions. It is evident that he is proud of his technical skills and the imagination needed to produce these illustrations.

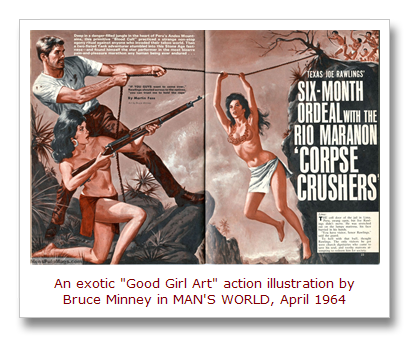

He should be proud. The technical skill and creativity that went into these works is mind boggling.

When you realize that he was given a one-paragraph summary of a story, had to come up with a concept, sketch it, shoot the models, and then paint the work in a week and a half, you cannot help but appreciate his talent.

Bruce admired his fellow artists, particularly Mort Kunstler, of whom he was also a bit jealous. His competitive nature comes out when he talks about Kunstler. He felt that he was as good as Kunstler, but lacked Mort’s confidence.

He has fond memories of Norm Eastman, Bob Schulz, John Duillo, Charles Copeland, and Rudy Nappi.

He knew many of his contemporaries by reputation only having met them by chance in Eddie Balcourt’s office or the waiting room of Magazine Management or Emtee, two of the major publishers of men’s adventure magazines.

They were kindred spirits, but they were also the competition. Men’s adventure magazine illustrators didn’t sit around at the Algonquin Hotel drinking and sharing stories.

They were working long hours in their studios creating works of art that are finally being recognized.

Here’s how Bruce described the way a typical job worked:

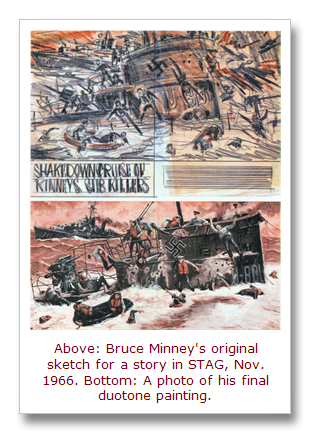

“I would get a call that they had a job for me. I would go into the city to meet with the art director. He would give me a one-paragraph synopsis of the story. I would then go home and do three pencil sketches. I always did three sketches. I never had a problem coming up with ideas for sketches. I read the paragraph describing the job and I could picture it in my head.

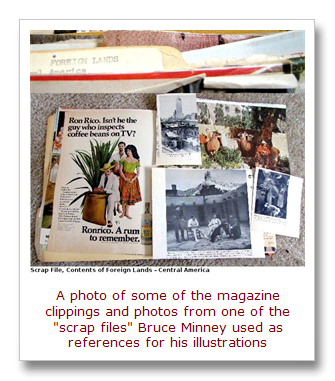

That’s what being an illustrator is all about. I had enough confidence in my abilities not to worry about coming up with ideas. I knew I could get it done. I was never terrified by white space. Deadlines didn’t affect me that much. If you were scared, you didn’t stand a chance. My biggest problem was finding good scrap [i.e., reference photos from magazines or other sources]. For some things, you needed a model to draw from, you couldn’t just make it up. I had tons of file folders with scrap. They were all indexed and organized. Every time I read a magazine, I would tear out pictures for my scrap file.

The sketches usually took a day or two. I would then go back to the city and show the sketches to the art director. He would approve one. In the beginning I used a professional photographer to shoot the pictures of the models.

It was expensive. When things got tight, I had my wife use our Polaroid camera and I would model. Eventually, artist Rudy Nappi taught me how to shoot and develop pictures and I did my own. [See Part 1 of the MensPulpMags.com interview with Bruce for more about that story.]

The whole process took about a week and a half. When I first started, I took the photos and manually blew them up on the drawing board. Later, after we moved to a bigger house, I got a Bausch & Lomb projector that would allow me to project the photos onto the board with the size I needed. The projector was invaluable and allowed me to work a lot faster.

I never had an art director reject my sketches. They always picked one. After I had the illustration laid out, I filled in the colors with watercolors. Then I added more detail with acrylics. Finally, I finished them in oils. This allowed me to build up and balance the colors.

Even if you weren’t happy with a piece, I learned early on that you never apologized for the work. Artists have a tendency to apologize because the work is never perfect. You see something that isn’t right and you want to apologize, but you can’t. You have to hold your tongue. If you made excuses, you didn’t last very long. You couldn’t say, ‘if I just had another day I could have tightened it up.’ Art directors didn’t want to hear that. They paid you for a job. If they didn’t like it, they wouldn’t use you again. I had a few of those with the paperbacks. With the magazines, I guess they liked what I did since they kept me employed for over 20 years.”

Acknowledgments…

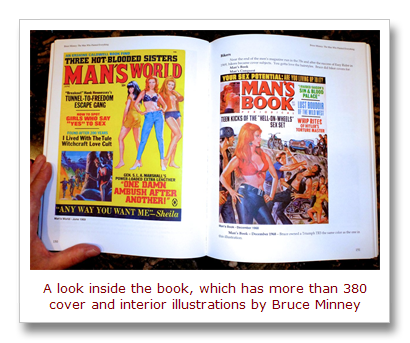

Many people helped with the book BRUCE MINNEY: THE MAN WHO PAINTED EVERYTHING.

First and foremost, I want to thank Bruce for dredging up memories of a long forgotten past. He was a trooper. Next, I want to thank my wife, Carole, for introducing me to her family and for all her support over the years. She was also a great editor. Thanks, too, to my brother-in-law Craig for his contributions, insights and modeling skills.

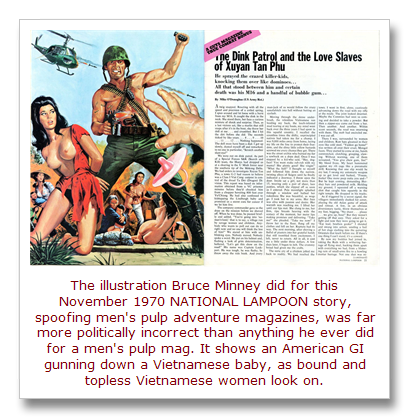

Thank you Mark Simonson, Proprietor of Mark’s Very Large National Lampoon Site for identifying the mystery interior Bruce did for National Lampoon. Thank you, TJ Duke, for tracking down interiors in the late 60s.

Finally, thank you, Bob Deis, creator of the MensPulpMags.com blog, for doing the interview with Bruce that inspired me to go further and write this book and for providing scans.

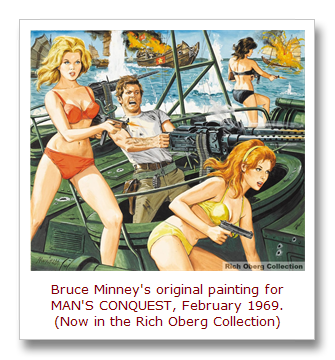

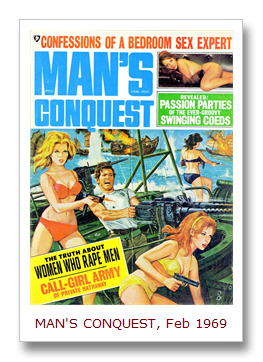

And last, but not least, a big thank you to Rich Oberg, whose collection of men’s adventure art and magazines helped us identify more of Bruce’s works then I ever thought possible. His enthusiasm for the genre is unmatched.

Editors Note: You’re very welcome, Tom. Thank YOU for creating such a terrific book about one of the best of the many great artists who worked for men’s adventure magazines and for sharing your guest posts with my readers.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on the Men’s Adventure Magazines Facebook Group.

More recommendations for fans of men’s pulp mags and vintage illustration art…