Some men’s adventure magazines of the ’50s and ’60s were mainstream and mild, like Argosy and True. The entry for Argosy in the 1957 edition of Writer’s Market said it wanted: “Articles of personal adventure – crime, humor, offbeat and exotic travel, treasure hunts, unusual outdoor stories – everything of interest to the active, intelligent male except overly sexy material.”

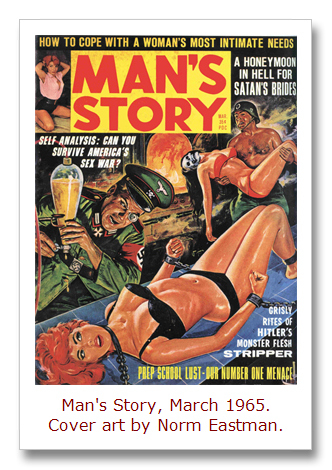

Other men’s postwar pulps – like Man’s Story and True Men Stories – were spicier and sexier. Some of the most sought after today are those that had elements many people would view as OTT, politically incorrect and offensive. Things like bondage and torture cover art by such artists as Norman Saunders and Norm Eastman, showing scantily clad nymphs being tormented by fiendish Nazis.

From a modern PC perspective, these and other aspects of men’s pulp mags are indeed sexist, racist, homophobic and xenophobic. (Additional *ists and *phobics may apply.) Of course, readers of the era didn’t see themselves that way.

A core target audience of men’s pulp mags of the ‘50s and ‘60s were World War II veterans. Men like my late father.

My dad was a high school dropout who enlisted in the Army at the height of the war. He went through combat hell in the South Pacific. Bullet-riddled beach landings on Japanese-held islands. Nerve-wracking patrols in the jungles of the Philippines. Yet, like many combat vets, my father also thought his years at war were the best years of his life. He told me so. Often.

|

The Greatest Generation (Tom Brokaw) |

When WWII ended, my dad – like many vets – worked in blue collar jobs and did his best to be a good provider for his family and a good father. And, in general, he was. He was a bona fide member of what Tom Brokaw has dubbed “The Greatest Generation.”

My dad was also sexist, racist, homophobic and xenophobic. (Additional *ists and *phobics also applied.) So were his surviving war buddies and most other straight adult white men at the time. They were the guys the men’s postwar pulp magazines were created for. Reading old copies of these vintage magazines today can help us understand “The Greatest Generation” in ways the history books can’t. Of course, they’re also mind-bogglingly entertaining. At least, they are to fans of the genre, like me.