[EDITOR’S NOTE: A link to a flip page copy of the first issue of BATTLE CRY magazine is at the bottom of this post.]

Memorial Day is a day to remember and honor the men and women who died while serving in the United States Armed Forces.

But it also makes me think of my late father, Robert Carl Deis, who served in the Army during World War II and survived.

Dad was a Scout and Rifleman in the 6th Infantry Division (specifically, G Company of the 1st Infantry Regiment). He saw hellish action in the South Pacific.

Like many veterans, when Dad came back to the States, he worked in blue collar jobs to support his family and struggled to understand and adjust to the enormous social changes that were taking place in the 1950s and 1960s.

American military veterans like my Dad and his Army buddies, who served and survived, were the primary audience for many of the men’s adventure magazines of the ‘50s and ‘60s.

And, there were millions of them.

In fact, there were nearly 16 million male veterans of World War II when that global conflict ended in 1945.

Some of them also fought in the Korean War, which began five years later. More than 5.7 million Americans served in that conflict by the time it ended in 1953.

Most of the 160 or so magazines in the men’s adventure genre were designed to appeal to the interests those veterans and, later, to the 8.7 million American men who served in the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1975.

Thus, almost all included war stories of various kinds: true history pieces and eyewitness accounts; serious dramatic war fiction; highly-embellished articles that mixed fact and fiction; and, wild over-the-top yarns featuring sadistic Nazis and Commies, scantily-clad babes, and battling Yanks. However, only some of men’s pulp adventure magazines had a specific focus on war.

They included: BATTLE CRY, BATTLEFIELD, BATTLE ATTACK, BATTLE STATION, MAN’S COMBAT, MEN IN COMBAT, REAL COMBAT STORIES, REAL WAR, SALVO, TRUE BATTLES OF WORLD WAR II, TRUE SPY AND WAR STORIES, TRUE WAR, TRUE WAR STORIES, WAR, WAR CRIMINALS, WAR STORIES, WAR STORY and WOMEN-IN-WAR.

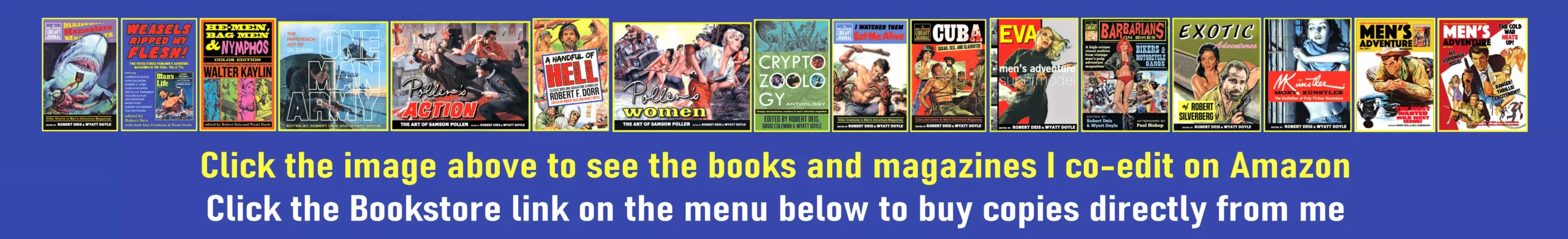

Most of the magazines in the war mag subgenre were fairly short-lived (as were many other magazines in the men’s adventure genre in general). The longest-lasting was BATTLE CRY. It was published from late 1955 to mid-1971 by Stanley Publications, Inc., the flagship company of pioneering comic book and magazine publisher Stanley P. Morse.

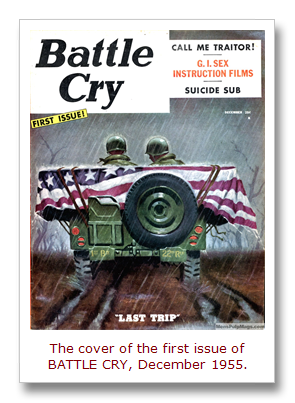

When the puritanical 1954 Comics Code essentially banned violent or sexy images in comics, Morse discontinued his BATTLE CRY comic book and created the men’s adventure magazine BATTLE CRY.

The comic had lasted for 20 issues. That’s why the first issue of the men’s adventure magazine version, dated December 1955, was numbered Vol. 1, No. 21.

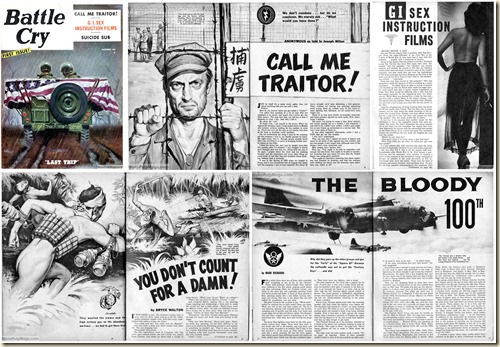

The first issue of BATTLE CRY magazine features a moving cover painting. Unfortunately, it’s uncredited. (My guess is that it may have been done by the great pulp illustration artist Clarence Doore, who did many of the early BATTLE CRY covers.) It shows two American GIs driving a jeep loaded with the flag-covered coffin of a fallen comrade. The words “LAST TRIP,” printed at the bottom of the cover, are the poignant title of the painting, not the title of a story inside.

On the contents page of this issue, there’s a fascinating introduction about the purpose of the magazine, presumably written by the magazine’s initial Editor, Harry Kantor.

This intro doesn’t mention anything about the transformation of the BATTLE CRY comic into a men’s adventure magazine.

Here’s how it explains the genesis and purpose of the new periodical:

WE’RE mad. Good and mad. P.O’ed.

This started because of something we overheard. We were reminiscing about the old days in England with the 8th AAF, when some joker butts in with, “The war’s over! When are you guys gonna forget it?” We didn’t answer him. We were too stunned to answer. But his remarks set us to thinking. And wondering.

We wondered if that’s how most people felt. “Forget about 1940-45, it’s over and done with. World War II and Korea are just history.”

Well, maybe so. But not to us who were in it. Especially those who shed some blood. We don’t forget that easily. Even if the others do. Korea was an example of that. Just a nice private little war. Only concerned those who were there and their families. Didn’t concern anyone else.

Well, that’s what we’re sore about. You don’t forget that easily. Or you shouldn’t. And that’s why this magazine. BATTLE CRY is to make sure you don’t forget.

What are our purposes? Our aims? Well, we’re not going off half-cocked and say that through these pages we hope to stop wars. We know that can’t happen. Even though we wish it could. Magazines don’t stop wars. People do.

But we felt that it’s about time people found out what war is really like. The frustrations, the fears, the anguish, the futility, and all of the rest that makes up combat and the military.

That’s why this magazine.

Another reason. Sixteen million present and ex-service men and women. Somewhere on these pages you’ll find something that interests you. That concerns you. A shot of your old outfit. A battle you fought in. A buddy you lost contact with. We’re trying to make this the postwar YANK. We’re trying to make this YOUR MAGAZINE.

No, we’re not forgetting we were once in The Service. We’re damned proud of it.

BATTLE CRY will help us to remember.

Inside the first issue of BATTLE CRY there are announcements of several regular features designed to let veterans communicate with each other — in the same way a modern Internet forum or Facebook group does for people who share certain interests.

For example, the “Whatever Happened To…” section was designated as a place where vets could post messages to old buddies they were trying to find or to announce dates and locations of reunions for their outfits. The “So You’re Out Now” feature was launched as an ongoing source of information about programs for veterans and to provide answers to questions vets sent in about problems they faced.

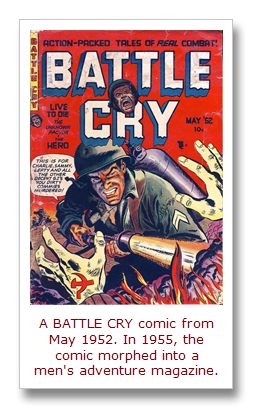

The articles and stories in the December 1955 issue of BATTLE CRY and other early issues are not the type of wild-and-crazy “sweat magazine” style yarns that were the primary content of most Stanley Publications magazines in the 1960s and early 1970s (including issues of BATTLE CRY published in those decades).

Many stories were gritty, but not lurid, non-fiction and fiction war stories, such as:

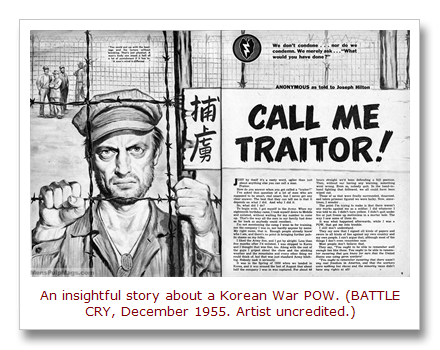

“CALL ME TRAITOR!,” an insightful “as told to” story about a soldier who was a prisoner of war in Korea;

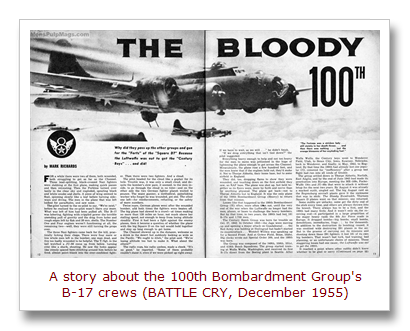

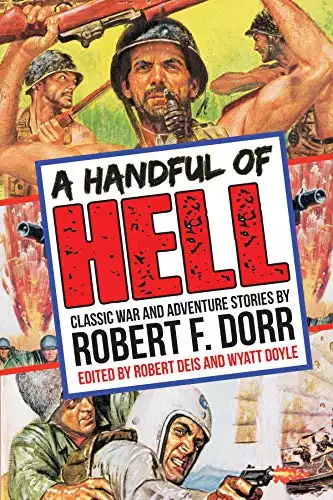

“THE BLOODY 100th,” a fact-based story about B-17 crews in the 100th Bombardment Group that reminded me of the history books MISSION TO BERLIN and MISSION TO TOKYO by the late men’s adventure magazine writer and military aviation historian Robert F. Dorr, whose classic MAM war and adventure stories are featured in our book A HANDFUL OF HELL;

“TANK TRAP,” another fact-based story, about WWII tank crews;

“WORLD’S TOUGHEST KILLERS IN KHAKI,” a salute to the Australian military;

“THE BLOODY BUTCHERS OF MILNE,” an account of the WWII Battle of Milne Bay in New Guinea

“YOU DON’T COUNT FOR A DAMN,” a ripping WWII fiction yarn;

“YA GOTTA KILL ‘EM TO TRAIN ‘EM,” an endorsement of tough basic training techniques;

“WHAT MEN THINK OF IN THE FACE OF DEATH,” another story about the bravery of American bomber crews, this time B-24 crews in the South Pacific; and,

“SUICIDE SUB,” a true story about the USS Tang, a famed WWII submarine that sank 33 Japanese ships before being sunk by a malfunctioning torpedo in 1945, killing most of the crew.

Not all of the stories in the first issue of BATTLE CRY are serious. For example, there’s an article about the often laughable “GI SEX INSTRUCTION FILMS” (a.k.a. sex hygiene films) that were supposed to educate American soldiers about how to avoid catching a venereal disease (or getting the local gals pregnant).

There’s a humorous story about the, uh, side benefits of serving behind the lines in an office that had female staff, titled “I WAS A FILING TIGER.”

And, as usual in vintage men’s pulp mags, there are advertisements that often provide unintended humor, like the oddly-placed ad about the power of prayer that’s sandwiched between ads for illustrated porn booklets on one of the back pages.

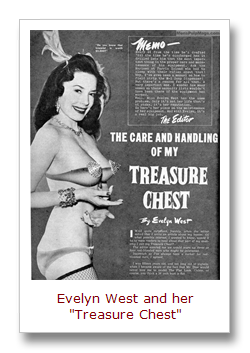

There are also some classic cheesecake photo spreads in this issue, featuring the famed stripper Evelyn “Treasure Chest” West, the alluring, somewhat notorious actress and model Francesca De Scoffa and a lesser-known pinup model named Lee Wilson.

In the 1960s, BATTLE CRY moved increasingly into “sweat magazine” territory and left behind many of the original goals outlined in the Editor’s introduction in the December 1955 issue.

Yet, as noted by vintage magazine expert Dr. David M. Earle, author of the excellent book ALL MAN!: HEMINGWAY, 1950s MEN’S MAGAZINES AND THE MASCULINE PERSONA, men’s adventure magazines published in both the ‘50s and ‘60s played an important role in the lives of America’s military veterans.

In an interview I did with Dr. Earle a while back, he explained:

“The most concentrated exploration of men’s adventure magazines that I make in the book, and which I find pretty enthralling and novel still, is how they offered veterans of World War II a means to deal with and categorize both their wartime experience and the difficulties of returning to United States. They returned to a society that was, for a large part, unaware of exactly how horrible their experiences had been. The bloody realities of the war had generally been censored by the government and avoided by the press.

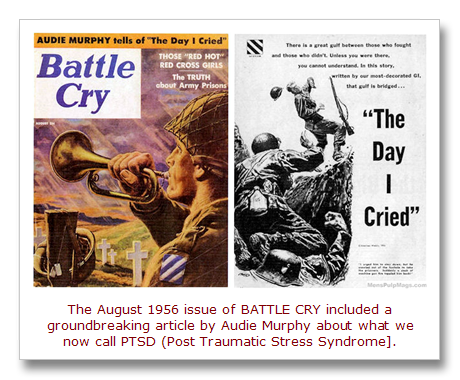

Yes. The end of the war was obviously a happy time, but also a very traumatic time: a difficult shift to a postwar economy, pressures of suburbanization, the simple difficulties of readjusting, and even the difficulty of expressing, to your family and yourself, the experience of war. Men’s adventure magazines like BATTLE CRY featured stories by and about vets, soldiering, battle. They offered columns for reuniting with former war buddies. They returned men to the camaraderie of soldiering, but in a safe place. The stories about war provided a text and narrative for vets to identify with. This is one of the important parts of healing for PTSD [Post Traumatic Stress Disorder], hence why ‘rap sessions’ were implemented for vets returning from the Vietnam War. Audie Murphy, the World War II hero who became a famous actor, wrote an amazing story about this for BATTLE CRY in 1956 [“The Day I Cried,” August 1956] that was instrumental in breaking the previous taboo about discussing war-related mental problems.

The aspects of men’s adventure magazines mentioned by Dr. Earle are front and center in the first issue of BATTLE CRY. It remains one of the best issues of the magazine from its early, pre-sweat mag years.

You can read a complete, high resolution, flip page copy of that issue by clicking this link or the image below.

In honor of Memorial Day, I am making it available for free to interested readers.

This one’s for you, Dad.

* * * * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on the Men’s Adventure Magazines Facebook Group.

|

Click this link or the image below to read a flip page copy of: BATTLE CRY, December 1955 This is a digital copy of the complete issue, in high resolution PDF format, featuring gritty war stories, classic pulp art, vintage cheesecake photos of Evelyn “Treasure Chest” West, and much more. |

RELATED READING AND LISTENING…