With  PulpFest 2025 coming soon (August 4-7 in Pittsburgh, PA). I’ve been thinking back to previous PulpFests I’ve enjoyed.

PulpFest 2025 coming soon (August 4-7 in Pittsburgh, PA). I’ve been thinking back to previous PulpFests I’ve enjoyed.

In case you didn’t know, PulpFest is one of the biggest and best annual pulp-related conventions in the country.

It’s a descendant of PulpCon, a pioneering event that ran annually from 1972 to 2008. In 2008, several pulp magazine experts who had been active in organizing PulpCon — Jack Cullers, Barry Traylor, Ed Hulse and Mike Chomko — decided to create a new pulp-related convention they named PulpFest.

To help attract people who are not just fans of the classic all-fiction pulp magazines published during the first half of the 20th century, they widened the focus welcoming sellers and creators of the wide variety of mediums influenced by the pulps — including comic books, action/adventure paperbacks, “new pulp” novels, and vintage men’s adventure magazines (MAMs) published form the late 1940s to the mid-1970s.

Their vision and the indefatigable organizing skills of a team of people, including William Lampkin, Sally Williams Cullers, and Craig McDonald, have kept PulpFest going strong ever since.

In 2018, Mike Chomko invited me and my Men’s Adventure Library publishing partner Wyatt Doyle to have a table at the show. He also asked us to make a presentation about some of the connections between the men’s adventure magazine genre and the earlier pulps. We took him up on both offers, had a great time, and have been going every year since then.

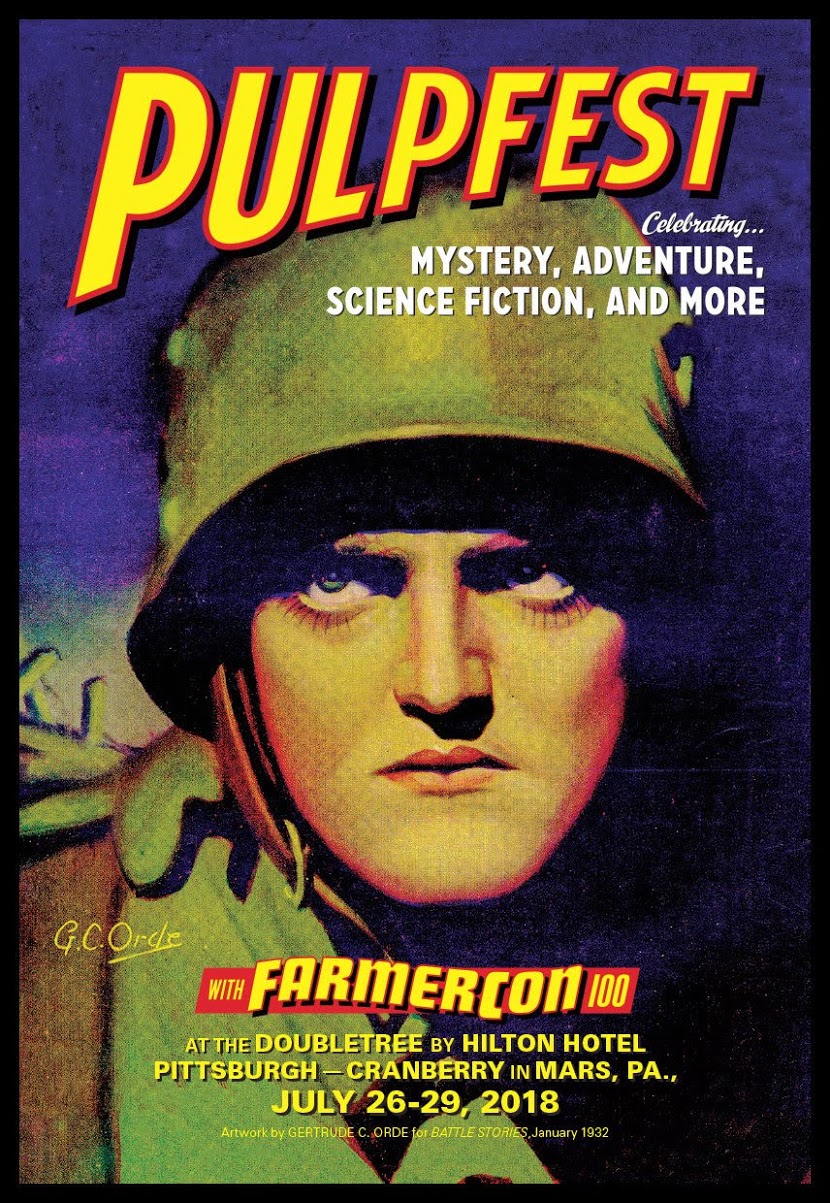

PulpFest is held at the DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Pittsburgh–Cranberry. It’s a nice hotel and the convention features  scores of dealers and many fascinating presentations by pulp culture mavens.

scores of dealers and many fascinating presentations by pulp culture mavens.

The theme for the 2018 PulpFest presentations was “The Pulps at War.” Mike asked Wyatt and I do a presentation about the war stories and artwork in MAMs and the thematic, artistic and literary DNA they share with pulp magazines.

Wyatt and I titled our presentation “Men’s Adventure Magazines and the Art of War.” This blog post provides an overview of what we discussed.

The golden era of pulp magazines came in the first half of the 20th Century. The World War II years are often cited as beginning of the end of the classic pulp mag genre. The years after WWII saw the beginning of the rise of men’s adventure magazines, which incorporated and continued key elements of the pulps, such as painted covers and rousing action/adventure stories.

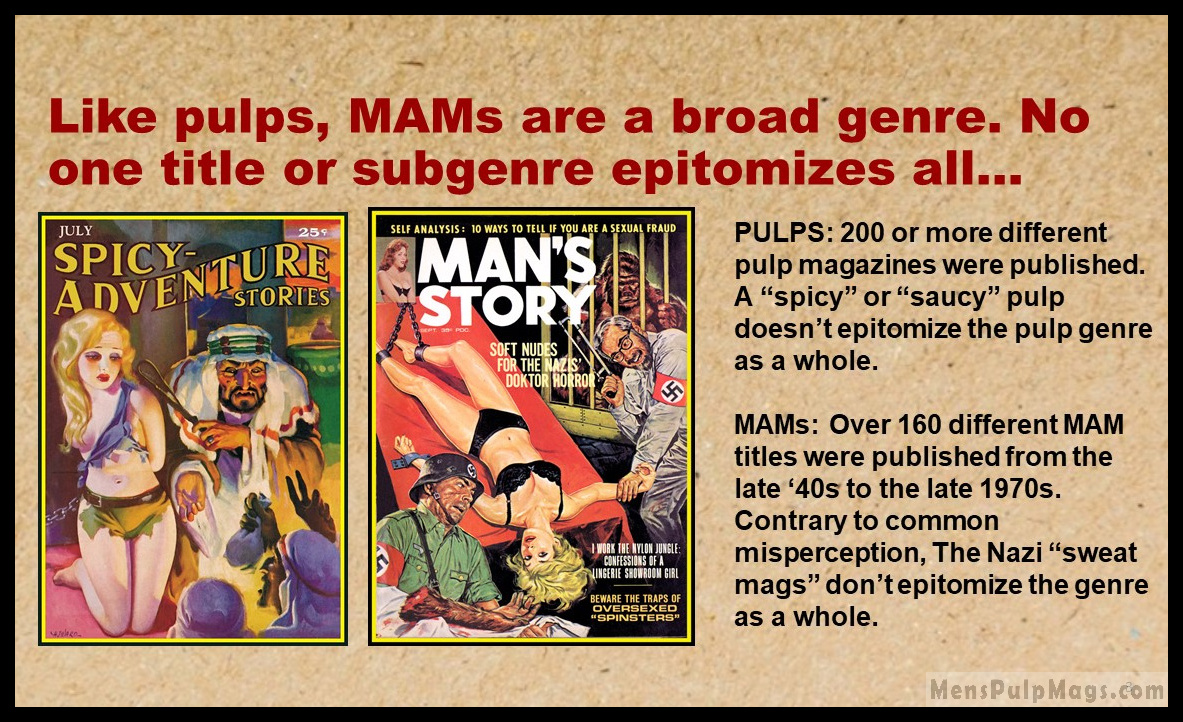

Fans know what someone means when they refer to “pulp magazines.” The simple, standard definition is that they are vintage, all fiction magazines printed on rough pulp paper that have painted covers and black-and-white line drawing interior illustrations. Fans also know that definition is a bit oversimplified.

Not all were printed on rough pulp paper. Not all had painted covers. Some included non-fiction articles. Basically, no one pulp magazine subgenre or title epitomizes all pulp magazines as a whole.

The types of stories in pulps cover a wide range of topics: war, exotic adventure, Westerns, crime, mystery, science fiction and fantasy, horror, romance, and more.

Some 200 or more different pulp magazine titles were published between the early 1900s and mid-1950s.

Some 200 or more different pulp magazine titles were published between the early 1900s and mid-1950s.

If you show someone who doesn’t know much about pulps the covers of issues in the “spicy pulp” subgenre or the “weird menace” subgenre (aka “shudder pulps”) their reaction would might be: “Wow, pulp mags must be some lurid, sadistic, sexist and racist form of periodicals.”

And, if they read some of the stories from mags in those outré subgenres, they might scoff at claims that pulp magazines published some of the best fiction stories of all time. But in fact, they did. They also featured some of the best cover and interior illustration art ever created. But it’s difficult to make generalizations that apply equally to all pulp magazines.

Each publisher and title had their own characteristics. In some cases, the stories and cover and interior artwork were created by top notch writers and artists. In other cases, the quality of the often quickly written, penny-word-word stories and illustrations aren’t considered great even by pulp fans.

The same is true of men’s adventure magazines. Like pulps, MAMs are a broad genre. More than 160 different titles that fit into the MAM genre were published. However, like pulps, no one MAM subgenre or magazine epitomizes all men’s adventure magazines as a whole.

Of course, many pulp mag fans learn to enjoy aspects of them all, the same way some movie fans can appreciate all types of movies, from the best, classic films to grade B action and horror flicks to the Grade Z movies spoofed by MST3K and the RiffTrax crew.

Of course, many pulp mag fans learn to enjoy aspects of them all, the same way some movie fans can appreciate all types of movies, from the best, classic films to grade B action and horror flicks to the Grade Z movies spoofed by MST3K and the RiffTrax crew.

Also, like pulps, each publisher and title had their own character. In some, the stories and cover artwork are great, truly top notch. In other cases, not so much – though if you become a true MAM fan, you learn to enjoy aspects of them all.

Many people have the faulty impression that the low-budget MAMs with covers and stories featuring sadistic Nazis tormenting scantily clad women are representative of MAMs as a whole. In fact, those lurid low-budget MAMs, which share DNA with the weird menace and spicy pulps, are really just a subgenre. It’s the subgroup of MAMs that frequently featured bondage-and-torture that I think fit the term “sweat magazines.”

Some people use that term to refer to all MAMs, but I don’t. And it wasn’t a term used by the publishers, editors and writers of those magazines. They typically called them men’s adventure magazines. Given the clear connections between pulp magazines and MAMs, some people also use the terms men’s pulp magazines or men’s pulp mags, for short, though I know there are pulp fans who get annoyed that the term pulp has come to have broader uses in recent decades.

At any rate, when you compare the war stories in pulps and the subgenre of war-themed pulp titles to the war stories in men’s adventure magazines and the war-themed MAM titles, you can see both the similarities and the differences between the two genres.

To prepare for our PulpFest 2018 presentation, I reread the chapter about war-themed pulp magazines in THE ART OF THE PULPS. That great book edited by pulp art collector extraordinaire Doug Ellis and pulp historian Ed Hulse, head honcho of Murania Press and editor of the “Blood ‘n’ Thunder” series.

To prepare for our PulpFest 2018 presentation, I reread the chapter about war-themed pulp magazines in THE ART OF THE PULPS. That great book edited by pulp art collector extraordinaire Doug Ellis and pulp historian Ed Hulse, head honcho of Murania Press and editor of the “Blood ‘n’ Thunder” series.

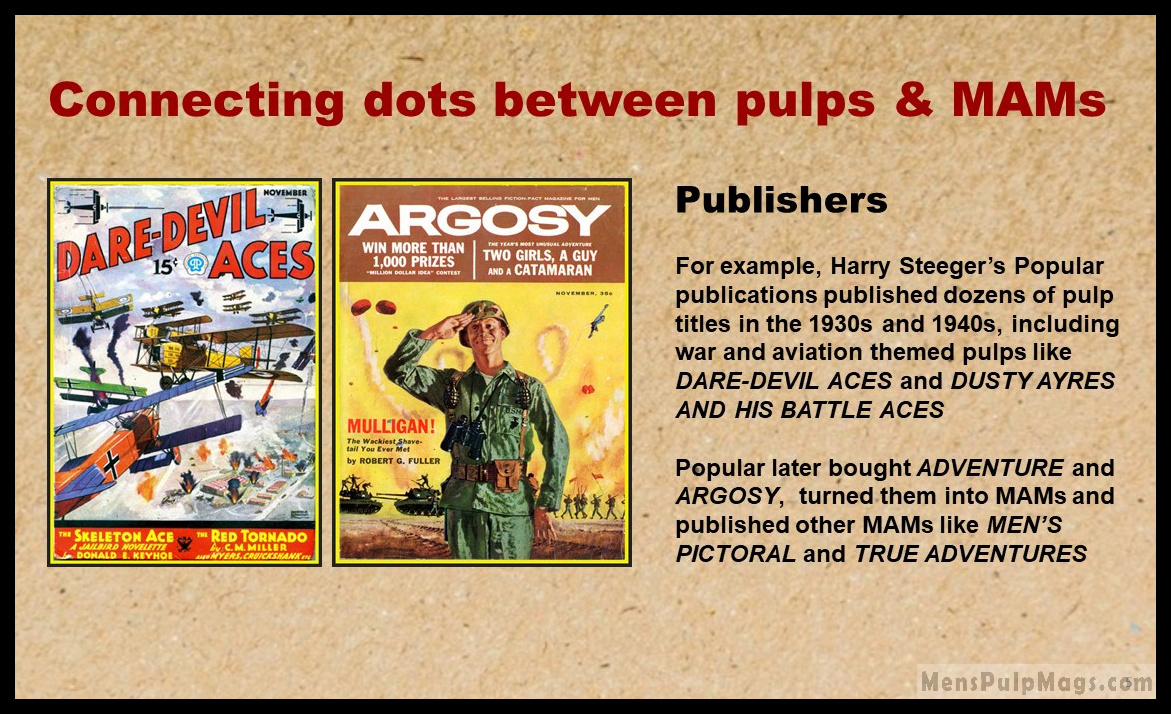

The chapter about war pulps includes many examples that can be used to connect the dots between pulps and MAMs. For instance, some of the pioneering pulps it discusses, such as ADVENTURE, ARGOSY and BLUE BOOK turned into men’s adventure magazines in the 1950s and pioneered the MAM genre.

Several pulp publishers also became publishers of men’s adventure magazines. One notable example is Harry Steeger’s Popular Publications. It published dozens of pulp titles in the 1930s and 1940s, including war and aviation themed pulps, like DARE -DEVIL ACES, G-8 AND HIS BATTLE ACES and DUSTY AYRES AND HIS BATTLE BIRDS.

Popular Publications later bought the long running pulps ADVENTURE and ARGOSY and turned them into men’s adventure magazines in the 1950s. Popular Publications also published the men’s adventure magazines MEN’S PICTORIAL and TRUE ADVENTURES. Pulp and physical fitness pioneer Bernarr Macfadden’s company published various pulps, including the aviation-themed war pulp FLYING STORIES.

Macfadden Publications later published the men’s adventure magazines SAGA, CLIMAX, IMPACT, PRIZE SEA STORIES and TRUE WAR STORIES. Fawcett Publications, founded by Wilford “Captain Billy” Fawcett, is another company that published both pulps and MAMs, though it’s more widely known for the its pioneering humor magazine CAPTAIN BILLY’S WHIZ BANG, MECHANIX ILLUSTRATED the Gold Medal paperbacks.

Fawcett’s flagship war pulp was BATTLE STORIES. It later published the hugely popular men’s magazines TRUE and CAVALIER, both of which fit into the men’s adventure magazines during part of their runs, and the lesser-known MAM TRUE THRILLS.

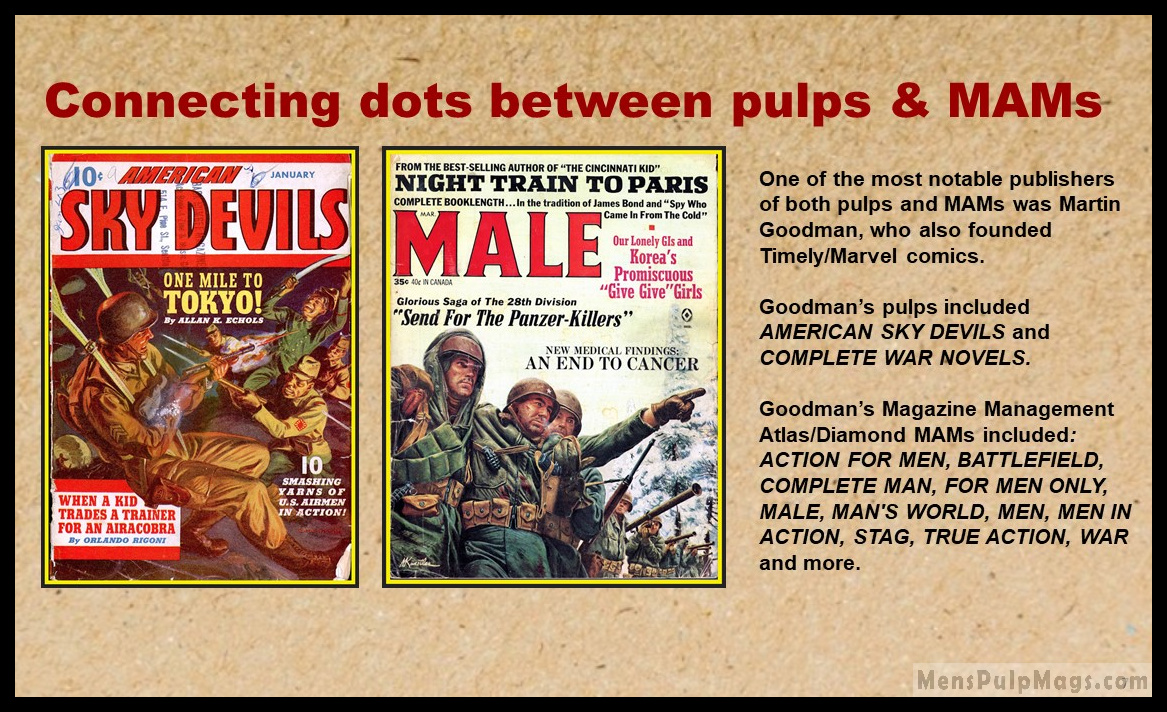

Marvel comics founder Martin Goodman’s publishing empire included dozens of pulp magazine in the 1930s and 1940s, through his companies Western Fiction Pub. Co, Red star, and Newsstand Group.

Marvel comics founder Martin Goodman’s publishing empire included dozens of pulp magazine in the 1930s and 1940s, through his companies Western Fiction Pub. Co, Red star, and Newsstand Group.

Two were war classic pulps: AMERICAN SKY DEVILS and COMPLETE WAR NOVELS.

Goodman went on to create one of the greatest lines of men’s adventure magazines, the ones often referred to as the Atlas/Diamond men’s adventure magazines. During the early ‘50s, Goodman’s MAMs were identified by the Atlas logo. After 1958, they were identified by a Diamond. The Atlas/Diamond MAMs include ACTION FOR MEN, ACTION LIFE, ADVENTURE LIFE, ADVENTURE TRAILS, BATTLEFIELD, COMPLETE MAN, FISHING ADVENTURES, FOR MEN ONLY, HUNTING ADVENTURES, KEN FOR MEN, MALE, MAN’S WORLD (SECOND SERIES), MEN, MEN IN ACTION, SPORT LIFE, SPORTSMAN, STAG, TRUE ACTION and WAR.

Many artists who did pulp cover art went on to do cover and interior artwork for men’s adventure magazines. Some of the best-known artists who worked for both genres are giants in the realm of pulp art, such as Walter Baumhofer, Rudolph Belarski, Clarence Doore, Mort Kunstler, Tom Lovell, Walter Popp, Norman Saunders, Rafael DeSoto and H. J. Ward.

Many writers also worked for both genres. Examples of writers whose work appeared in both pulps and MAMs include: Robert Bloch, Ray Bradbury, Edwin V. Burkholder, Arthur C. Clarke, Harlan Ellison, Erle Stanley Gardner, David Goodis, Frank Kane, MacKinlay Kantor, Day Keene, Gerald Kersh, Donald Keyhoe, Ed Lacy, Louis L’Amour, Elmore Leonard, John D. MacDonald, Richard Matheson, Talbot Mundy, Richard Prather, Ellery Queen, Robert Silverberg, Mickey Spillane, Theodore Sturgeon, A.E. Van Vogt, Robert Turner and Bryce Walton.

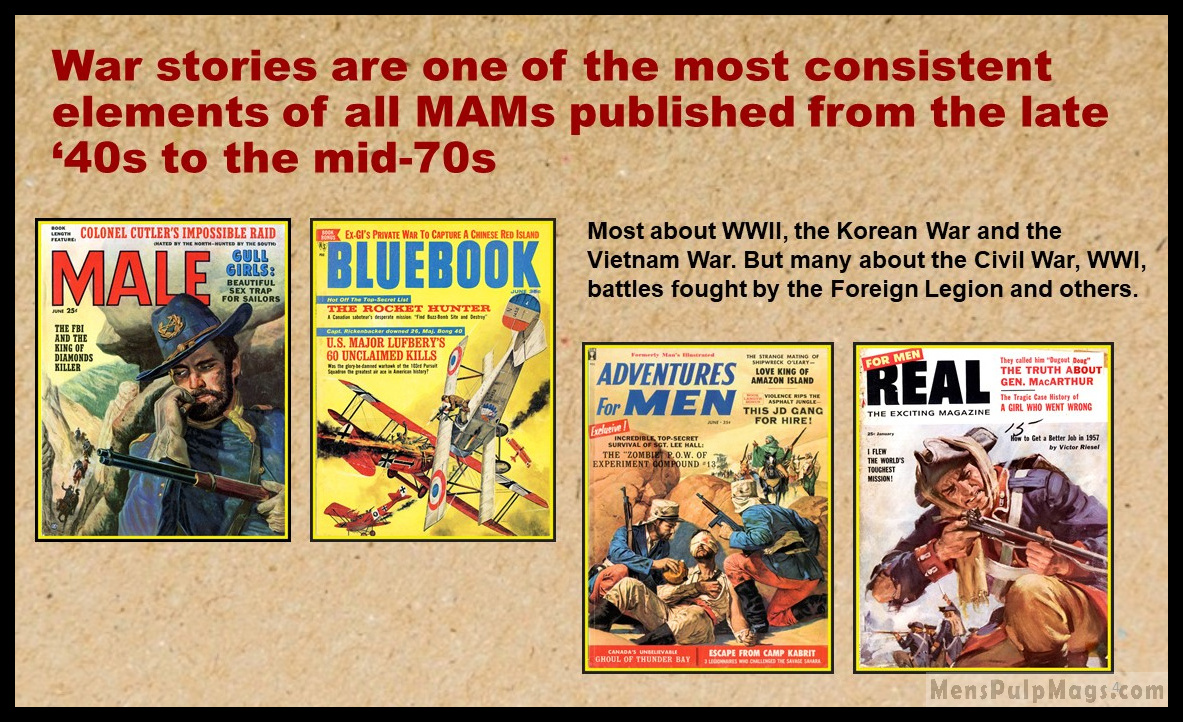

War stories – both fiction and non-fiction – were a common feature in men’s adventure magazines throughout all three decades of their existence, as were advice and expose stories and news features specifically geared for veterans and active duty serviceman. Like pulps, some lasted for three decades. Some only for only a few issues. Some only one.

War stories – both fiction and non-fiction – were a common feature in men’s adventure magazines throughout all three decades of their existence, as were advice and expose stories and news features specifically geared for veterans and active duty serviceman. Like pulps, some lasted for three decades. Some only for only a few issues. Some only one.

There are many different kinds of stories in MAMs – but war stories were one of the most common throughout the genre’s three-decade lifespan. This makes sense given that military veterans and servicemen were the main target audience for most MAMs, especially in the 1950s and early 1960s. There were nearly 16 million male veterans of World War II when it ended in 1945. Some of them also fought in the Korean War, which began five years later.

More than 5.7 million Americans served in that conflict by the time it ended in 1953. Most of the 160 or so magazines in the men’s adventure genre were designed to appeal to the interests of those veterans and, later, to the 8.7 million American men who served in the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1975.

Thus, almost all included war stories of various kinds: true history pieces and eyewitness accounts; serious dramatic war fiction; highly embellished articles that mixed fact and fiction; and, wild over-the-top yarns featuring sadistic Nazis and Commies, scantily clad babes, and battling Yanks.

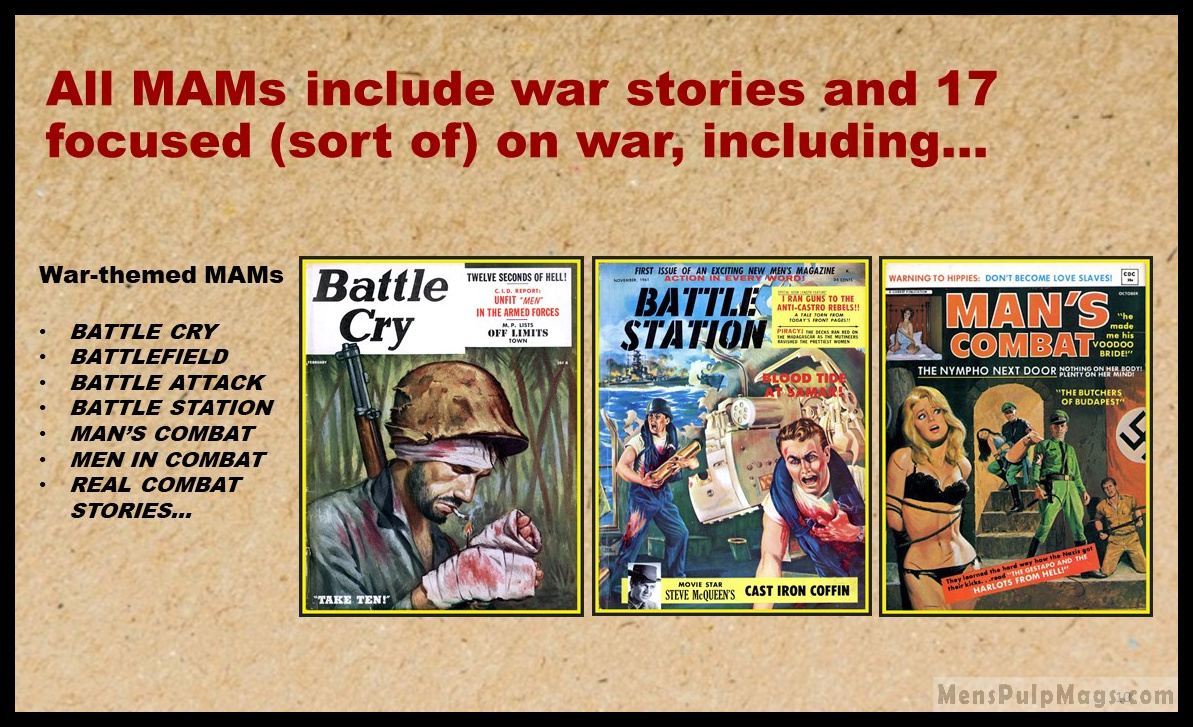

However, only some MAM titles had a specific focus on war. They include: BATTLE CRY, BATTLEFIELD, BATTLE ATTACK, BATTLE STATION, MAN’S COMBAT, MEN IN COMBAT, REAL COMBAT STORIES, REAL WAR, SALVO, TRUE BATTLES OF WORLD WAR II, TRUE SPY AND WAR STORIES, TRUE WAR, TRUE WAR STORIES, WAR, WAR CRIMINALS, WAR STORIES, WAR STORY and WOMEN-IN-WAR. Most of the magazines in the war mag subgenre were fairly short-lived (as were many other magazines in the men’s adventure genre in general).

However, only some MAM titles had a specific focus on war. They include: BATTLE CRY, BATTLEFIELD, BATTLE ATTACK, BATTLE STATION, MAN’S COMBAT, MEN IN COMBAT, REAL COMBAT STORIES, REAL WAR, SALVO, TRUE BATTLES OF WORLD WAR II, TRUE SPY AND WAR STORIES, TRUE WAR, TRUE WAR STORIES, WAR, WAR CRIMINALS, WAR STORIES, WAR STORY and WOMEN-IN-WAR. Most of the magazines in the war mag subgenre were fairly short-lived (as were many other magazines in the men’s adventure genre in general).

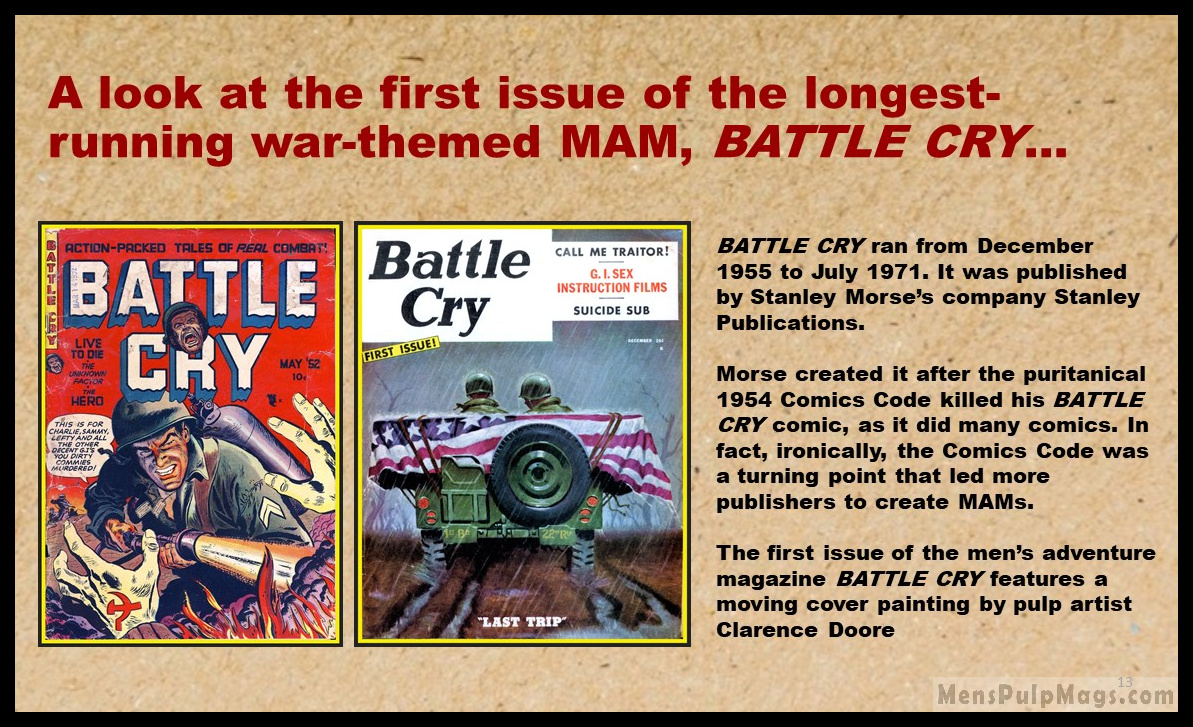

The longest-lasting was BATTLE CRY. It was published from late 1955 to mid-1971 by Stanley Publications, Inc., the flagship company of pioneering comic book and magazine publisher Stanley P. Morse. Before BATTLE CRY the magazine, Morse published the comic BATTLE CRY, of many war-themed comic books that were popular from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s. Then, in 1954, the puritanical 1954 Comics Code banned violent or sexy images in comics. That killed off many horror comics – and the bloodier war comics. But Stanley Morse was a smart publisher. He discontinued his BATTLE CRY comic book and turned it into the men’s adventure magazine BATTLE CRY.

The BATTLE CRY comic had lasted for 20 issues. That’s why the first issue of the men’s adventure magazine BATTLE CRY, dated December 1955, is numbered Vol. 1, No. 21. The first issue of BATTLE CRY magazine features a moving cover painting by Clarence Doore.

It shows two American GIs driving a jeep loaded with the flag-covered coffin of a fallen comrade. The words “LAST TRIP,” printed at the bottom of the cover, are the poignant title of the painting, not the title of a story inside.

It shows two American GIs driving a jeep loaded with the flag-covered coffin of a fallen comrade. The words “LAST TRIP,” printed at the bottom of the cover, are the poignant title of the painting, not the title of a story inside.

The BATTLE CRY comic had lasted for 20 issues. That’s why the first issue of the men’s adventure magazine BATTLE CRY, dated December 1955, is numbered Vol. 1, No. 21. The first issue of BATTLE CRY magazine features a moving cover painting by Clarence Doore. You can see an in-depth post about that first BATTLE CRY issue at this link.

At PulpFest 2025, my Men’s Adventure Library co-editor Wyatt Doyle will be making a presentation on Friday, August 8 at 6:55pm titled “Masters of Men’s Adventure Magazines.” The PulpFest schedule of events shows me listed for that presentation, too, but unfortunately my wife has a health issue that prevents me from going this year. I will be there in spirit and Wyatt will have a table where he’ll be selling and signing our books. My MEN’S ADVENTURE QUARTERLY co-editor Bill Cunningham will also be there, selling and signing MAQ issues 1 through 12 and copies of other cool books he’s designed and published.

Hopefully, I’ll see them and our many PulpFest friends at PulpFest 2026.

* * * * * * * *

Comments? Corrections? Post them on the Weasels Ripped My Book Facebook Page, email them to me, or join the Men’s Adventure Magazines & Books Facebook Group and post them there.

Related reading…